- Home

- Anson Cameron

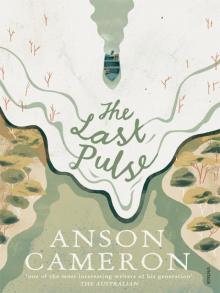

The Last Pulse

The Last Pulse Read online

About the Book

A blackly funny novel about an unlikely hero, and his misadventures on the flood he has created.

In the drought-stricken Riverland town of Bartel in South Australia, after the suicide of his wife, Merv Rossiter has an epiphany. He trucks north with his eight-year-old daughter, Em, into Queensland. There he blows the dam at Karoo Station sky high, releasing a surging torrent through outback New South Wales into South Australia.

As the authorities frantically search for the culprits, Merv and Em ride the flood south in a stolen boat, rescuing a bedraggled Queensland Minister from her floating portaloo, and an indignant young blackfella who fancies he sang the river to life all by himself.

Meanwhile, in Canberra, the political flotsam carried by Merv’s renegade ocean brings the Federal Government to its knees.

Wryly humorous, poignant, timely, The Last Pulse is Anson Cameron’s finest work to date.

Contents

Cover

About the Book

Title Page

The Last Pulse

About the Author

Also by Anson Cameron

Copyright Notice

Loved the book?

In the faint hope of denying the delusion you have when you imagine you are not one of the fools you see around you, well … here’s this.

Prologue

The woman left the house barefoot carrying a heavy stool with a length of electrical flex draped over her shoulders. The flywire door slammed and bounced and clicked closed, bringing the dog around the corner of the house at a run. It circled her, squirming and leaping, and ran ahead and then back to her and ahead again. She set down the stool and called it and hooked her hand in its collar and dragged it back to the house and flung it inside skidding across the lino and slammed the door.

She picked up the stool again and crossed the dead garden. A butcherbird sang its daylight song in a gum above the dry river. In the great shed that contained Merv’s workshop, where their daughter was forbidden to go, she placed the stool beneath an angle-iron roof truss and stood on it and looped the flex over the truss and tied a clove hitch and jerked it tight. From the house she could hear the dog howling and she frowned at it momentarily. She tied the flex to itself with a slip-knot and put the noose she had made over her head and ran it up tight around her neck and stepped off the stool kicking it over backward with her bare heels.

As she hung there her toes scraped lines in the red sand that filmed the concrete slab and the world distended in her bloating eyes and she sucked breaths like hauling beasts from mud and tried to lift herself on the taut flex above and then to force her fingers between it and her throat. When her carotid artery burst her lifeblood arced once, twice, thrice … across the sandy floor blending with the sump-oil stains while her world blacked to a point.

A month later her widower, Mervyn Rossiter, still numb enough to be drawn to and transfixed by daytime television, was sitting alone at home in his underfurnished farmhouse outside Bartel in South Australia watching a talk show from England.

JEREMY PAXMAN INTERVIEW WITH EGYPTIAN PRESIDENT MOHAMED HANBAL. JUNE 2009. COLLINS HOUSE, OXFORD STREET, LONDON.

PAXMAN (contemplative, legs crossed, wrinkled brow): President Hanbal, there was a report in The Wall Street Journal in May that the Ethiopian government has consulted a German engineering firm to do a feasibility study on building a dam on the Nile. How does your government respond to that report, considering almost all of Egypt’s agriculture depends on that river?

HANBAL (smiling): Our neighbours, the Ethiopians, are a gracious and wise people who would not contemplate damming this sacred river on which we have relied for many thousands of years. (Stares at camera, lowers voice.) However, were they to be so proud, greedy and foolhardy as to build a dam, then our air force would bomb it to gravel like that. (Snaps his thumb across his finger.)

Merv held his cracked hands out at the TV and nodded slowly, a proselyte finally hearing the truth he had been waiting for. Then rubbed his palms together making a sound like pumice on hide. ‘Yes,’ he whispered, snapping his finger across his thumb in imitation of the Egyptian President, loud enough in the empty house to cause the dog to stand and stare at him, cocking its head in wonder. ‘Ethiopia,’ he explained. ‘Egypt,’ he told the dog.

Dillandbundy is a town on a flat grey plain that has been cleared of its trees and covered by grazing cattle and a chequerboard of cotton fields. Its main street is paved by triangles of shade made by polypropylene sails that palpitate overhead in the breeze like the palates of a thousand toads. Most travellers driving into this town look about and wonder if they have enough petrol to get to the next, for if it does not thrill the hearts of its citizens (and it does not – they are leaden and morose, with looped reminiscences of fisherman’s baskets eaten in Gold Coast bistros playing in their heads keeping their day-to-day reality at bay), it positively frightens strangers. Look around. Its people are stooped by a heavy resentment, fatigued with an overproof jealousy. The rest of the world is better than Dillandbundy and they have the mind-curdling luck to live here. So don’t expect Dillandbundyans to be welcoming when you drive into town from a better place.

Merv Rossiter has driven from South Australia and parked outside the Dillandbundy pub in his Mack Trident twenty-six metre B-double semi. Atop the trailer is a large aluminium boat with a cabin and twin outboards. Unusual and illegal to park a vehicle so big in the main street. Pedestrians frown at the thing. A parking officer moseys uptown called from his bacon and egg burger by this illegal leviathan. He takes a photo from north to south along the street and strolls past the brute before capturing it again from south to north. He taps on the truck door and when Merv lowers the window says, ‘Sir, you’re illegally parked in fifteen parallel parks. It’s fifteen tickets. That’s how it’s calculated. Not one offence. It’s fifteen. And another fifteen for every quarter hour from now.’ He smiles up at the curly-haired malefactor as if he were offering him the cat-o’-nine-tails. ‘That’s sixty tickets an hour.’

Merv has a blinking disgust on his face like he’s staring at a paedophile through fog. He stares at every Queenslander as if he’s staring at a paedophile through fog. His face is as ruined as any farmer’s; the skin cured dark with sun and wind and the features wrung with worry and puffed with grog. The hand he hangs out the window is massive, shiny-hard and as meshed with cracks as ancient porcelain. He nods down at the parking officer as if impressed at the fate being revealed. ‘Sixty an hour’s big business,’ he smiles.

Merv doesn’t own this truck or anything else of value now. His farm has been laid waste, his livelihood taken, his good nature largely poisoned, and his wife killed. By Queensland, he would say. He would like to see this parking guy and his town council cohorts try and impound the truck. ‘I don’t reckon you could write sixty tickets an hour. Anyway, you don’t look as if you could keep it up for long before you knocked up.’

‘Are you going to move your truck, sir?’

Merv’s daughter Em crawls from the bunk behind his seat and across his lap and, taking hold of the steering wheel, leans out and looks down to see who her father is talking to. She is pale-faced and sleepy-haired with large green eyes, a scrawny kid from a black and white photo. You don’t see many kids who aren’t chubby these days. The man doesn’t smile at her like most adults do at kids, so she decides on a peace-offering. ‘What’s brown and sticky?’ she asks. The parking man shakes his head and says, ‘A stick.’ Em disappears inside the truck cabin and nods at her father that the man got it right, and the man nods his head also at having seen another adversary off.

‘What if I was to tell you this truck was broken down?’ Merv asks.

‘You’ll still get the tickets. You

can challenge them in court if you have a legitimate reason. But you gotta get’em.’ He puts his hands on his hips.

‘But you wouldn’t tow it or anything stupid like that?’

‘We haven’t got anything could tow this truck in Dillandbundy. We could call the tow truck from St George, but that’s, like, our last resort. I haven’t done that for three years because last time the truck owner moved his truck when the towie had just got here to tow it and the towie was so angry he called me prawn-head.’

‘Your hair’s spiky, your face is pink and your eyes are black and bulgy. You think he called you prawn-head because he was pissed off? I think he might have been a marine biologist moonlighting as a tow truck driver.’

‘Are you going to move your truck, sir?’

‘You already stole everything I own. Now you want me to pay seven million parking fines?’

‘I haven’t stolen anything from you, sir. And with that accusation, and with what you implied about my head, I must warn you our conversation is now being recorded for legal reasons.’ The parking guy reaches down and turns on his portable voice recorder. This is a device issued to parking inspectors by the shire to prevent those officers being abused, accused and slapped around by incensed citizens. They have not succeeded in this prevention as much as in capturing the joy of parking officers’ humiliation for all to hear. With the inception of this device a meeting of shire administration staff on the third Friday afternoon of every month has become traditional. At which meeting the administration staff sit around laughing as they play the tapes and listen to truckies blow fuses and kick parking inspectors’ arses and farmers lose it and question the morality and courage and breeding of their parking officers and school mums snarl like fornicating cats and highlight the physical unloveliness of the parking officers and speculate on the same-sex proclivities they might have.

‘A recording?’ Merv asks. ‘So, sort of like a record of everything I say?’

‘A legal proof of our exchange, sir. I deem what you said about me being a thief sufficient cause to activate my recorder.’

Merv climbs down from his cab and stands squarely in front of the inspector, pointing at and looking at and speaking to his voice recorder.

‘Okay, then. If you are hearing this legal proof of my and Prawn-head’s exchange, you thieving bastards, then I guess that means the water’s on its way south and this you’re listening to now is a famous bite of sound. So here’s what I say: You declared war on us and I brought the war to you. You thought you could starve people without us rising up. You made laws that said you could ruin my world and you thought they were good laws. You thought water that had always run to a place had no right to run and no rightful place to go. Or maybe you didn’t even bother to think that out. Maybe you never got past seeing something and saying, “That’s mine,” and grabbing it and not giving a flying what-he-said about who or what that killed. You are thieves and I wish I lived upstream of you. Then we’d see you suck on a dry disappointment of ruined life. Let’s go have lunch, Em.’ (This last sentence, with its familiar diminutive, was much replayed by the police, trying to divine the speaker’s identity.)

The parking inspector has heard as much abuse and as many threats over the years as parking inspectors naturally deserve. But he has never heard anything like this. This abuse seems more general than normal. Not as personally directed. And what was that about war? The parking inspector is inclined to call the police, but he knows the police are as likely to call him ‘prawn-head’ as the tow truck drivers.

He watches Merv and his daughter cross the road hand-in-hand to the Dillandbundy Diner. ‘I’m writing the tickets,’ he calls. ‘E, U, X, 7, 4, 2, 8.’ The truck’s registration. ‘Ah, a Crow Eater.’

Merv drinks a coffee. Em has a toasted ham and cheese sandwich and a strawberry milkshake. The shop lady rested her hand on top of the milkshake maker while it buzzed and the hammock of fat hanging beneath her arm shook like a squid working a jackhammer. Em looked at it. Looked away. Had to look back. The fat squidishness of that lady’s arm has made the shake taste like fish.

Through the window of the diner they watch the parking inspector scribbling furiously on his pad trying to fill tickets out at one-a-minute. Jumping up on the truck’s running board to stick each one to the wind-screen. ‘Why did that prawn-head man call you a Crow Eater, Merv?’

‘I don’t know …’ he makes his voice low with regret. ‘You eat one crow and they never let you forget.’

She looks into his eyes, which are wide with a theatrical sadness, then shakes her head. ‘You didn’t eat a crow.’

‘You finish your breakfast. Lunch is going to be late, by the time we get on the boat.’

The Party Animal is a nine metre aluminium party punt built to hold work functions and Christmas parties choofing out of Bartel up and down the Murray River. There is a lot of open space up front for dancing and partying, under which is a cabin with bunks and a toilet and shower. A pilot’s shack sits amidships and a fishing area out back.

A month ago Merv had seen it moored at the jetty in Bartel and liked the look of its shallow draft. It seemed a vessel that could navigate floods and swamps and shallows. He had left a note taped to its cabin door telling the owner he was interested in purchasing it. Then gone to the front bar of the Bartel Hotel and drunk two pots of beer while looking down at the river watching The Party Animal out the window. By the time he’d finished the second pot it seemed stupid not to take the damned boat, considering the favour he was going to do its owner and how he was going to lift them all up and save them in the near future. Beer made the concept of private property questionable and he felt the community owed him a boat. All men feel like this at times, with beer, about communities. So he went home and got his stock trailer and came back and cut the chains off the boat and rode it downstream to the ramp and winched it up out of the river and drove it back to the farm where Em danced around yelling, ‘A boat. A boat.’ Before stopping and saying, ‘But, Daddy, we don’t have any water.’

‘Em, my silly little beast,’ he told her, ‘we are going to take the boat to the water.’

‘Good,’ she said. ‘That’s the easiest way.’

The levee at Karoo Station runs out across the Culgoa floodplain toward a dusty pre-horizon. On its high side is a catchment bay of choppy brown water with a forest of dead trees reaching through its surface running north with the ancient bed of the Culgoa River somewhere in its gut. On the levee’s low side is the scrub of the dry floodplain and the Culgoa River itself oozing through the concrete sluice in the levee. Thin in its wide bed it wanders away south beneath the gums with its head held high, whistling, its hands in its pockets, kicking at stones, pretending not to care about its reduced state.

On this side of the valley the levee ends at high ground above the catchment bay and on this high ground today stand two marquees hung with maroon bunting. Each is topped with a long silver pennant flapping southward from a spire and on the pennants the words ‘KAROO STATION’. On one marquee a sign reads: ‘KAROO STATION WELCOMES MINISTER WRAY.’

On the dusty floodplain below the marquees are a hundred or so cars parked in rows. From them a satin rope and a path of plastic lawn leads their owners up to a green swathe of plastic lawn between the marquees, and on this artificial Eden stand the assembled dignitaries of the Dillandbundy Shire dressed in yesteryear’s suits and Akubra hats and frocks tailored for dugongs, which the middle-aged women of Queensland resemble in their morphology. They are being served a bubbling wine and a local beer by waitresses in black dresses with white aprons. They are a stout people built by a stodgy cuisine, a jovial people, but there is not one of them who won’t let rapine, dressed in a tuxedo and introduced as Private Enterprise, work to their betterment.

They are Queenslanders. They live on a frontier in a moment of opportunity. They have grasped that opportunity and made the best of being at the head of a long food chain. And if that fortune has attracted outside criticis

m that has made them defensive, insular and suspicious of the rest of Australia, then that suspicion is a small price to pay for the smorgasbord of their rapine at which they have become porky-faced and at which they have clad their hearts in fat.

This afternoon the sun is shining, Champagne is being quaffed and a lunch is in the offing, a happy announcement is to be made, the designated drivers are chosen … a grand day is shaping. Hello, Dawn. Great to see you, Geoff. G’day, Ken. Smithy, you old bastard. That sort of thing.

Dressed in an aubergine suit that hints at a rakish confidence, Reg Auster, Chairman of the Karoo Group, is nevertheless trying not to radiate the self-importance he feels. His face is showing no triumph or pride, his hands are clasped before him like a vicar’s. He’s playing it cool. Keeping it real. Displaying a knack for false humility. All these invited guests are here for his announcement. Everyone here has a stake. The health and wealth of Karoo will wash out into the surrounding community. They have come here today to hear Chairman Reg tell them what he has done for them. They have come for good news and, as the afternoon progresses, to sing shickered hallelujahs to Reg and pop corks from recognised vintages and stomp up dust and cheer the beautiful future on, while their designated drivers smile at the private hijinks of movers and shakers.

‘Come on, Reg. Don’t be a pain. A quarter million meg? I heard a quarter million meg. That’s the figure people are saying.’ Sally Carruthers is a reporter with Radio 4STG in St George. She went to Ipswich Grammar with Reg’s daughter Caroline and as a family friend expects a scoop when he has one.

‘Sal, Sal, Sal … all will be revealed over lunch. I can’t steal the company’s thunder just because you rowed with Caro.’

Boyhoodlum

Boyhoodlum Nice Shootin' Cowboy

Nice Shootin' Cowboy Pepsi Bears and Other Stories

Pepsi Bears and Other Stories The Last Pulse

The Last Pulse Stealing Picasso

Stealing Picasso Silences Long Gone

Silences Long Gone